Navigating the Silence: Social Isolation and Loneliness Among Older Adults

In an age where connectivity seems ubiquitous, loneliness and social isolation can dramatically affect the health of older Americans. Recent findings by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), backed by the AARP Foundation highlight the severe health impacts of social isolation and loneliness, particularly among low-income, underserved, and vulnerable subpopulations.

This report indicates that over a third of adults over the age of 45 experience loneliness, and about a quarter of those aged 65 and older are viewed as socially isolated.1 Older adults face a higher risk of both loneliness and social isolation due to factors such as living alone, the loss of family or friends, chronic illness, and hearing loss.

Social isolation is the shortage of social connections and can be a precursor to loneliness, whereas loneliness can manifest regardless of how much social interaction one has. As seen in the National Health and Aging Trends Study that found 24 percent of community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older in the United States were categorized as being socially isolated and 4 percent were severely socially isolated.2 It’s a misconception to assume that all older people are isolated or lonely. Rather, older adults are at increased risk. Throughout their lives, the experience of social isolation and loneliness can be intermittent or persistent, depending on an individual’s circumstances and perceptions.

Impacts of Loneliness on Health

The impacts of social isolation and loneliness are bi-directional. Studies have shown links to increased risks of premature death, dementia, heart disease, and stroke, even rivaling well-known health risks such as smoking and obesity. Social isolation and loneliness not only causally affect health but are also influenced by one’s health status. For instance, a chronic condition may serve as both a risk factor for and a consequence of social isolation or loneliness. Specifically, social isolation is associated with a roughly 50 percent increased risk of developing dementia. Furthermore, certain groups, including low-income, minority, and LGBTQ+ elders, are particularly vulnerable to these health risks due to social determinants of health.

Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) can be found in our recently released Social Determinants of Health Data Collection.

Mapping Social Isolation Risk Factors

At PolicyMap, we can leverage geospatial data to visualize areas with high concentrations of at-risk populations, revealing patterns and risk factors that can inform targeted interventions. The NASEM report emphasizes that specific subgroups of older adults, such as immigrants, LGBTQ+ individuals, and minorities, face even higher risks of social isolation and loneliness. We recently expanded the American Community Survey (ACS) Census variables which can help to better understand the landscape of our communities.

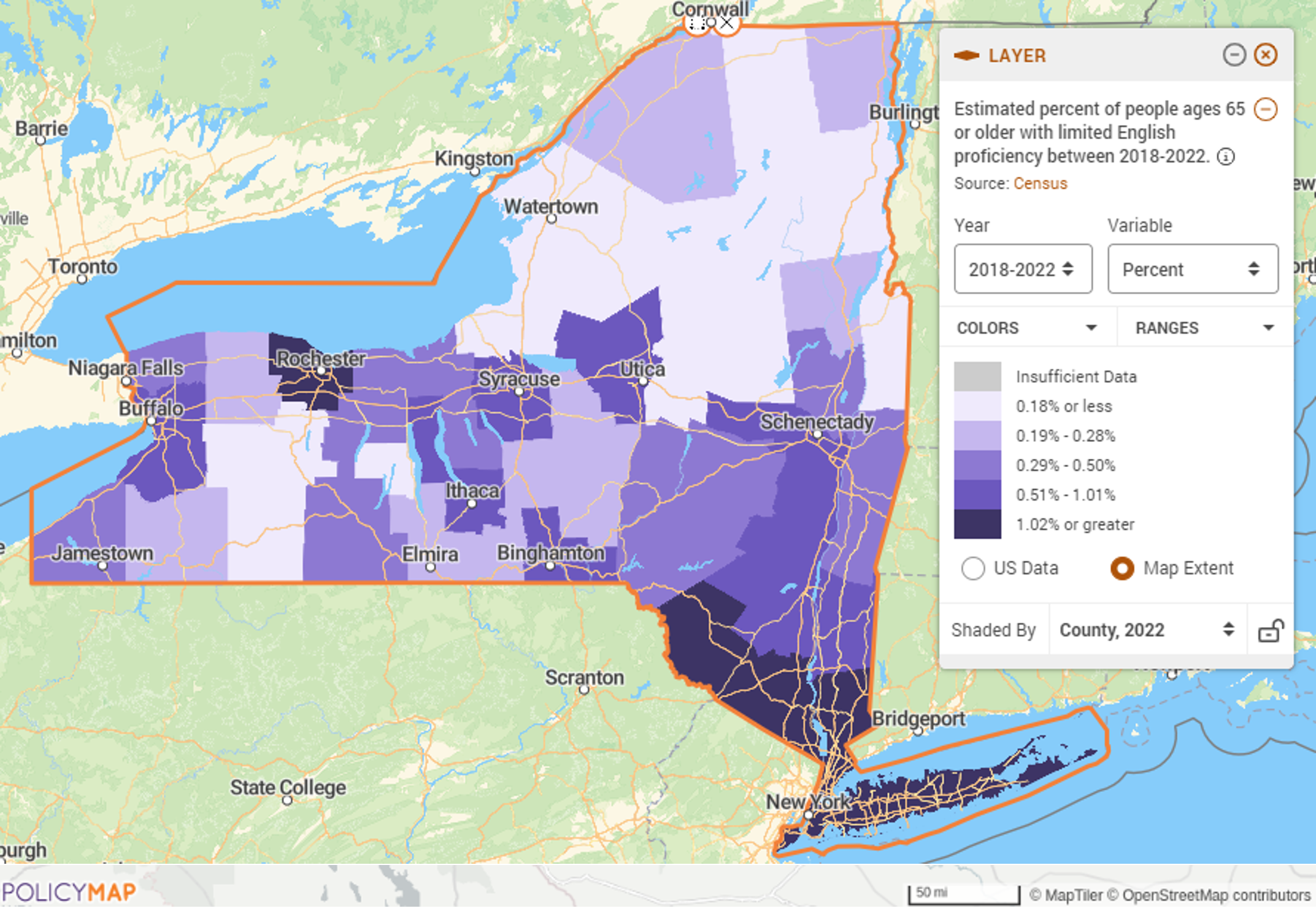

Key variables include seniors living alone and non-English speaking seniors, which help identify communities at risk of linguistic isolation. This data is crucial as living alone and language barriers significantly contribute to social isolation, particularly among diverse elderly populations.

The map below shows the percentage of people 65 or older with limited English proficiency by counties in New York.

Understanding Loneliness Risk Factors

Gathering specific data on social isolation is challenging; therefore, the report looks to proxy data for risk factors and lists four categories to consider: Physical Health Factors, Social and Cultural Factors, Social Environmental Factors, and Psychological, Psychiatric, and Cognitive Factors. For example, depression, anxiety, and cognitive declines, including social withdrawal seen in conditions like Alzheimer’s disease, are both causes and effects of social isolation and loneliness.

The map below shows Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Chronic Conditions data, specifically the percent of individuals enrolled in the traditional Medicare program who are diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia for counties in New York.

Creating a Multi-Layer Map

Our platform enables users to create a multi-layer map to explore the intersectionality of multiple risk factors. The multi-layer map feature will shade only those places that meet the parameters the user sets in the legend. The map below includes parameters to find the census tracts with the highest concentration of the following three risk factors:

- Homeowners 65+ who are burdened by housing costs

- Non-family householder 65 + living alone

- Percent of people 65+ with limited English proficiency

Click here for more help creating a multi-layer map.

Challenges & Opportunities

While PolicyMap can help provide valuable insights, it also highlights the need for more comprehensive data collection and research, particularly concerning underserved and vulnerable groups. The current datasets, though informative, underscore the necessity for ongoing enhancements to accurately capture the full spectrum of social isolation and its impacts.

As additional data becomes available, the PolicyMap team will continuously evaluate and integrate new datasets.

Request More Information

We invite policymakers, community leaders, and healthcare providers to utilize our platform to create effective, data-driven strategies that address loneliness and social isolation among our senior populations.

Interested in learning more about how to use PolicyMap to visualize the impacts of social isolation and loneliness? Fill in the form below to request more information.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25663. ↩︎

- Cudjoe TKM, Roth DL, Szanton SL, Wolff JL, Boyd CM, Thorpe RJ. The Epidemiology of Social Isolation: National Health and Aging Trends Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020 Jan 1;75(1):107-113. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby037. PMID: 29590462; PMCID: PMC7179802. ↩︎